Submachine 10 questions

July 21, 2015

So, guys, here’s the thing.

As you probably know, sometime ago I asked you to send me questions that you think should be addressed in the upcoming Submachine 10. Your response was swift, precise and… uhm… avalanche-like? Not sure if that’s the right expression. Anyway. I’ve collected 112 questions, and as you can imagine, I will not be able to answer them all in the upcoming game. Not even close. Maybe I should just write a book about Submachine. Like a dictionary, or digest.

I’m pretty sure I will cover some of those questions in Submachine 10, however I believe rest of them will have to wait for standalone Submachine games that will come later on. Those, while being stripped from the main storyline, will have plenty of room to discuss all those subjects in question. So, more Submachines, yay.

Here’s the full list of Submachine questions I’m supposed to tackle:

- In Submachine 9, the Player see the graves of Mur and Liz. Are they actually dead?

- Is the Player dead and the Submachine is some sort of purgatory?

- What really is the submachine

- who Mur and Liz really are

- who are all the others that explored the maze of the network of places we have been

- Was it all just a dream, an amazing place existing in the mind of the character we play as, or is this a story of someone traveling to a place we all want to visit, where travel is done by a machine, a portal and such?

- What’s so important in the fifth layer

- why don’t we ever see the main character

- elaborate a bit more on the plan

- How humans discovered the Subnet, the layers

- why Murtaugh (and Liz?) were chosen

- What was Shiva’s intention

- why the structure prevailed after the deaths of Mur and Liz

- Did the Player’s journey have some purpose?

- How did the Player begin all this

- where did he come from

- Who is the player?

- what time period is he living in compared to when Mur and Liz were alive?

- I would like if it gets cleared up if there is time travel involved in the series and in what way.

- why the karmic portals are destroying the subnet,

- what implications this has for the submachines and the player

- further explanantion to the time layer

- how Thoth and Shiva are both involved

- And where is Einstein?

- Clearly even if the player can’t interact with Mur, Liz, or Einstein directly, they’ve interacted with each other directly at some point – how can they have done so but none of the other people in the subnet have encountered each other?

- Where is sunshine_bunnygirl_17

- how much more connection there was with Covert Front.

- if there will be answers about the nature of the Submachine (location.. infinite? growing?…).

- Where are the corpses of people lived in the submahine?

- Is it possible the player was everyone of them in his/her past?

- Who buried the lighthouse and why?

- Did the events that the game discusses happen centuries ago or did the player participate in them?

- Will we ever see an actual human character?

- what happened to all the other, unnamed people who left notes throughout the Submachine?

- Where did they all go?

- Or were they ever really there?

- Why did Mur and Liz die?

- How could we talked with Mur, not so long time before his death?

- Why we didn’t meet anyone in Submachine?

- explain the links between different parts, so that we know if we are travelling in time and/or space/dimensions

- if everything is happening in chronological order.

- how Mur and Elizabeth came from that hostile situation between each other to that marvelous plot twist on sub9.

- In sub6 , where we have to hack the system, did human create/build that place ??

- I’d to know who and why created Wisdom gems and what they really are

- Are we alone?

- Why are we

- Kim był Mur i Elizabeth jak to się stalo, że się poznali, a może razem pracowali nad czymś?

- czy tą grę da się ukończyc?

- czy postać w którą się wcielamy kiedykolwiek wyjdzie z submachine?

- Kto tym wszystkim steruje po smierci Mur?

- Can we just see M’s face?

- Or atleast is arm?

- Einstein, how he is able to transport himself through portals and such, but where did he end off?

- everything what has happened in the subnet is the reality, or the machine was done in order that the persons were living in a virtual reality because in the earth or the reality happened a collapse, for this way saying, the apocalypse?

- How important the light is?

- more about what happens when you create a portal inside a portal

- things about the history of the submachine, at least the history that’s connected to humans somehow, knowing more about how the humans found the subnet (did someone create it and other people found it later on?

- did humans just stumble upon it somehow and decided to add their own creations to it? how did that happen?

- is there something outside the Submachine?

- How Sub_1 fits in with the overall plot since it’s brief story

- I finally want to know what those bells are exactly for!

- Where is Kent? a submachine location or a place on Earth?

- What’s the connection between submachine and Earth/The computer that surpassed human inteligence?

- What’s the connection between the Kent waterfall and karma?

- What is the rough timeline of the events in the series?

- ow do the places we visit in the series fit within the structure of the Submachine, and how are they connected? For example: which layer(s) were we during Sub1-Sub6? Did we travel from the Outer Rim to the Core at the end of Sub1?

- Who is Shiva/the Computer? Are they one and the same?

- Where’s the Loop in respect to the 8 Layers?

- Do Defense Systems and Subbots operate in all the Layers of Reality?

- Does the Plan have anything to do with the cubic shape of each room?

- Are the persons who wrote the notes in latest Submachines the former Basement Exploration Team?

- How did he get to Subverse and Basement from Sub1?

- Did he has some special purpose in Sub1-Sub4 except escape from the trap?

- If Subbots do exist in subverse…Show them and tell about them at least in one note, please?

- What connection do Sub0, SubFLF, SubFLF HD, Sub32 have with main series?

- Who are protagonists of these side games? Their purposes?

- What does “MAP” symbol mean? (Symbol we can see in all submachine games’ main menu)

- Why does ikentt have karma flow/water?

- Where is it located?

- Why there were excursions in Winter Palace, South Garden and Lighthouse?

- Does “our real world” exist at all in Submachine game universe?

- Did we really make time travel in Sub2, or in some other game?

- How is important the time in Submachine universe?

- How many people organizations are there?

- What is the company? (Sub4 Ship note)

- What organization ordered to scientist who called this place as “Submerged Machine” to work with submachine?

- What is Fourth Dynasty?

- What happened with “Temple/Murtaugh/Shiva Cult” (Sub9)?

- What happened with Lab workers? How did they ended there at all?

- From what organization are guys from Sub8?

- Who are guys from Sub9 secret notes?

- Is there God? aka Shiva Or all is just technology? aka Computer (or something like this…)

- explanation what happened in Sub2 intro and Sub2 outro…

- If we/Payer have one-dimensional mind (Sub9 secret note), then why do we can’t meet any people in Submachines? What is the problem?

- Way in the past you talked about the creator of the first Submachine, and how his creation went haywire. I would very much like to get to know how he reacted to it and felt about it all. He seems like such an important, yet underrepresented character.

- What happened to Henry O’Toole when “Murtaugh’s” religion began gaining traction. Was he forgotten or did his works become widely acknowledged.

- How do the people of the Subnet see their history, which eras do they revere and which do they condemn. Related to this, maybe we could finally get the sub-eras if not explained, at least listed.

- Murtaugh is a surname, you’ve admitted as much. What was Murtaugh’s first name?

- Are we alone in Submachine? Is there something there, lurking in the shadows, or are we just the only explorer traversing the subnet?

- Will the Third Layer ever be repaired and brought whole again?

- In Sub_9’s super secret bonus area, it was mentioned that Murtaugh was shown the future by Shiva that left him quite happy before he died. Perhaps this is what he saw? Perhaps we, the Players, will have our hands / cursors on this kind of conclusion?

- Who happened to commission the Submachine network (if it can be called that)?

- Why is there no life, inside the Submachine?

- What was the need for the limited appearance of firearms in Submachine? (Think I remember seeing something akin to a machine gun, in one of the games? Not sure.)

- What is the purpose of the cultural deities in Submachine?

- What happened to the notes we have collected along the way, with the exception of Sub5 notes?

- Who put the golden seals in Murtaugh and Elizabeth’s tombs?

- What is the purpose of the four symbols we see in Sub2? We never used them in the game.

- Where did Murtaugh obtain plans to draw the teleporter in the lighthouse

- Who was the man that left mentioned in Sub7, and why did he leave, did he also have power like Murtaugh’s?

- Why did Murtaugh teleport to the loop? What happened that caused him to enter the loop and not some random location in the outer rim, or is the loop the outer rim?

- sub4 – What on earth is behind the metal plate? (beginning on the roof)

Submachine 1 LP by Markiplier

June 14, 2015

Big shout out to all people who have suggested Submachine to him for months, or even years.

Thank you so much!

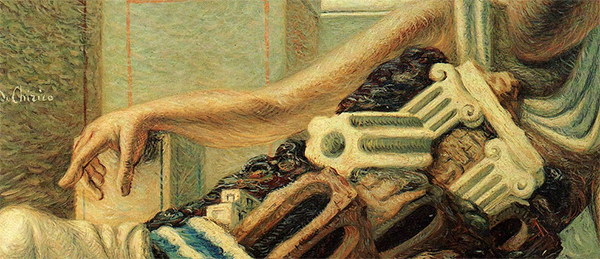

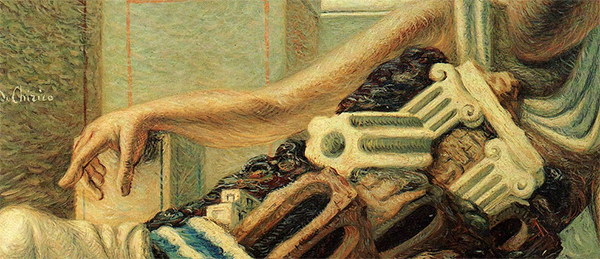

De Chirico and Submachine – the object of mystery

March 23, 2015

Text by — Federico Scarfo’

Translation by — Julia Perry and Federica Vecchio

You know how in a dream your brain has the power to mix pieces of places, houses, streets, statues, visited in the past and create a new and unique image as well as the ability to evoke familiar sentiments which for some reason, you have never actually experienced before? This is a major theme that unites two incredibly different things: the metaphysical painting of DeChirico and, in my opinion, an unfortunate series of “aim and click” flash games. I define it unfortunate because, being more than sure that an introduction to the Greek artist is not needed at all, the same cannot be said for Submachine: belonging to the unlucky class of flash games, that is to say games which you can play for free on the original site and which usually last for a limited period of time, the series has not gained the popularity I think it so long deserves. Although Submachine has never been an “innovator” of these games, initiated by legendary games like “The Secret of Monkey Island” and “Clock Tower”, I think it is more than suitable for flash games, especially because it has a minimalistic yet very interesting story, inspired by the Matrix, that incentivizes the player to pay great attention to the few clues given. The plot is trivial, the main character is trapped in the submachine, a specific machine that replicates an infinite number of closed environments, among which it is possible to travel through portals. Nevertheless, the most relevant points of strength of the game are its setting, graphics and sound effects: elements that are, as we say, abstract. In fact they are deeply linked to De Chirico’s thematic guidelines, those that were selected for the art show “De Chirico and the mysterious object”. The show, held at Villa Reale, that is the principal reason behind this article. As the title itself suggests, referring mostly to the paintings where the mysterious object is represented, the art exposure concentrates almost entirely on De Chirico’s relationship with objects, inanimate figures, opposed to living beings.

As I have already stated, the first point of similarity is the looming scenario on its single components, generating an oppressive, scary and dreamlike environment. In the painting “Mercurio’s meditation”, the feeling of claustrophobia is alimented by the prospective and narrow space, at the end of which lies a classic bust, the closest thing to a person that ever appears both in the metaphysic way of painting as well as in certain sections of Submachine. Similarly, painting by De Chirico set in an outdoor environment are just as disturbing, as they form a dreamlike composition whose limits are incumbent upon the flat sky and largely geometric shadows and solid walls.

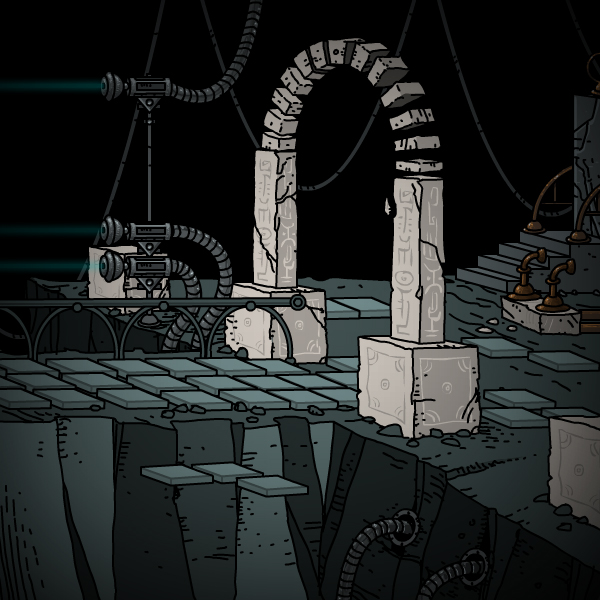

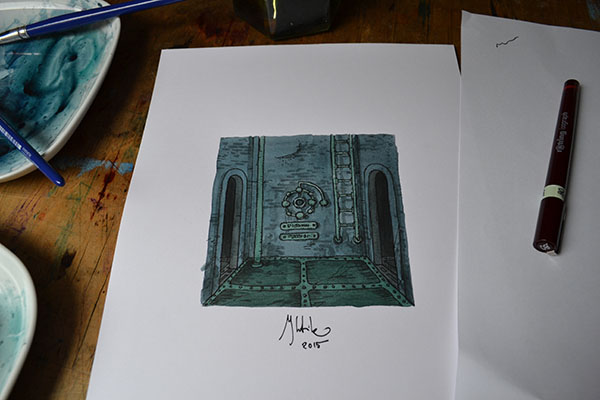

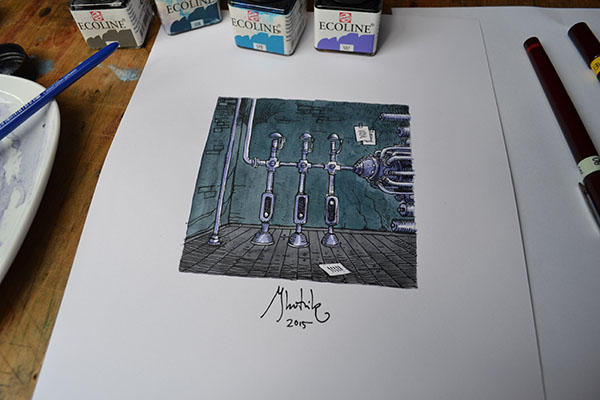

Submachine is set in a series of places, mainly closed, artificial and mostly ruined. For example, in the same episode, taking advantage of the portals in the game play, the character visits a ship, a canteen, a ruined coffin, the ruins of a temple, and various other places, in which it is easy to see Skutnik’s peculiar style. Each of these locations is abandoned, ruined, no longer functioning, and the themes of deterioration and dissipation melt with the feeling of claustrophobia, of falling out of place, of being undesired guests.

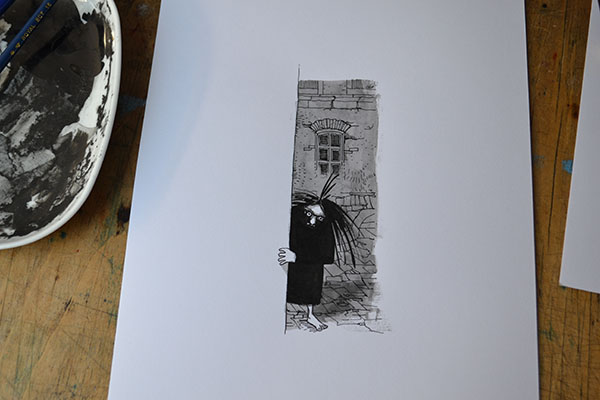

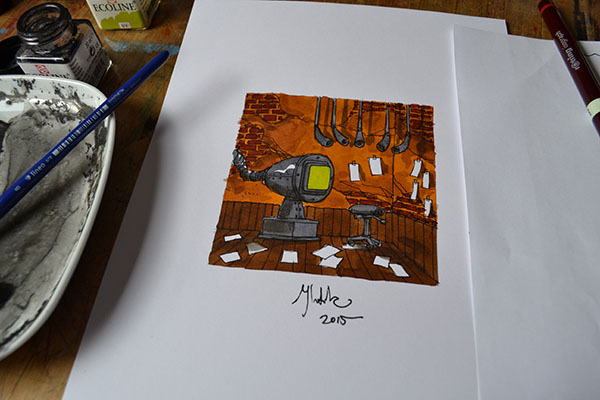

The second common feature derives from a second sense, that of loneliness. In most metaphysical painting, and in each section of Submachine, no human presence can be found. In Submachine, however, even recent traces can be found, which is surprising given the decrepitude of its surrounding environments. Most of the story is told through notes left behind by people less fortunate either long dead or who were forced to flee. The only human contact of the series takes place via computer and not coincidentally, happens to be one-sided since our hero does not have a keyboard to use. Isolation is the greatest power of Submachine, the “enemy” machine, due to its immensity and ability to forever grow and expand, pulverizing humans and objects in its way. The feeling of loneliness in De Chirico, however, come from a surreal feeling of familiarity. De Chirico represented environments as seen from a train window, wanting to reproduce the feeling you get when passing a nearby city and feeling a bigger sense of homeliness than its people. This maps an intimate representation of a place in each of us. The feeling of familiarity that Submachine’s location communicates is instead one linked to despair of the hunted, the ones who lost in the woods, recognize the real horror of aimlessly traveling in circles.

Lastly, the last common feature is the prominent role given to the objects. Like in “silent lives” or in the series of the “mysterious object” by De Chirico, in which objects are placed on a stage and in spite of the human figures portrayed faceless in the background., Submachine makes the objects the fundamental element. In fact, what else makes us realize how importance objects are if not a game in which taking advantage of the environment at its fullest? Everything that is useful exists in Submachine, an object, a note or a pattern, there are virtually no secondary characters, and if there are, they remain invisible throughout the entire series and bring interaction only through notes. In contrast, the statues, representations of steam-punk style potted machines are ubiquitous, mimicking what you would expect, the “real” world beyond the Submachine (although throughout history, the “true” world is not an external reality to Submachine). For their use and even for a sense of “company” that can be drawn from it – after all, they’re the only allies of a player playing against fate – objects are humanized in Submachine and from this it is humanization that becomes a sort of invincible enemy of the Submachine itself, that is far from being a simple virtual help, it becomes an opponent capable of smarts and immense resources, that reigns over an infinite space in which the relationship between object and humans is broken, and the only audible sound is one of squeaking machinery, moving, non-human symphonies that accompany the metaphysical framework that is the game.

De Chirico e Submachine – l’oggetto misterioso

Teso di – Federico Scarfo’

Avete presente quando in un sogno, mischiando pezzi di vari posti visitati in passato, case, strade, statue, il vostro cervello riesce a ricreare un’immagine unica, inquietante per la sua capacità di evocare sentimenti familiari ma allo stesso tempo di mantenersi estranea ed aliena? Ecco, questo è uno dei temi principali che accomuna due cose disperatamente diverse: la pittura metafisica di De Chirico e la a mio parere sfortunata serie di flash games punta e clicca del graphic artist polacco Mateusz Skutnik, Submachine. Dico sfortunata perchè, essendo più che sicuro di non aver bisogno di fare una presentazione del pittore greco, lo stesso non vale per Submachine: appartenente alla razza sfigata dei flash games, ovvero giochi a cui si può tranquillamente giocare gratis sul sito d’origine e che tendono a essere piuttosto brevi, il riconoscimento di cui gode la serie è stato sempre meno che risonante. Nonostante Submachine non sia mai stato un “innovatore” del genere punta e clicca, inaugurato da giochi leggendari come “The Secret of Monkey Island“e “Clock Tower“, a mio avviso possiede una giocabilità eccellente per un flash game, unita a una storia minimale e interessante, alla Matrix, che spinge il giocatore a fare tesoro dei pochi indizi che trasudano dal velo opaco del gameplay. Della trama si capisce che il protagonista è intrappolato nella Submachine, una macchina che replica virtualmente un numero infinito di aree chiuse, tra le quali si può viaggiare tramite portali. Tuttavia, il vero punto di forza della serie sono l’ambientazione, la grafica e il sonoro, elementi, per l’appunto, metafisici. Infatti si collegano con numerosi rimandi alle linee tematiche di De Chirico selezionate per la mostra “De Chirico e l’oggetto misterioso“, a Villa Reale, che è stata per l’appunto il motus primus di questo articolo. Come suggerisce il titolo stesso, ammiccante soprattutto alla serie di quadri ritraenti “l’oggetto misterioso”, la mostra si è concentrata principalmente sul rapporto di De Chirico con gli oggetti, le figure inanimate, opposte e surrogate del vivente.

Come ho già introdotto, il primo punto di similitudine è l’incombere dello scenario sulle sue singole componenti, generando un ambiente oppressivo, pauroso, onirico. Nel quadro “La Meditazione di Mercurio“, la sensazione di claustrofobia è alimentata dallo spazio prospettico, angusto, in fondo al quale giace un busto classico, la cosa più simile a una persona che appare sia nella pittura metafisica, sia in certe sezioni di Submachine. Allo stesso modo, i quadri di De Chirico ambientati in un ambiente esterno non risultano meno inquietanti, poiché formano una composizione onirica i cui limiti incombenti sono il cielo piatto e le ombre larghe e geometriche, non meno solide dei muri. Submachine è ambientata in una serie di luoghi, per la maggior parte chiusi, artificiali e perlopiù in rovina. Per esempio, in uno stesso episodio, sfruttando l’elemento di gameplay dei portali, il personaggio visita una nave, una cantina, la sezione di una tomba in rovina, resti di un tempio, e vari altri posti, nei quali è facile distinguere il tocco dello stile singolare di Skutnik. Ognuna di queste location è abbandonata a se stessa, in rovina, malfunzionante, e la tematica della bruttura e della decadenza si mescola con la sensazione di claustrofobia, di essere fuori posto, e di essere ospiti non desiderati.

La seconda caratteristica comune deriva da una seconda sensazione, quella della solitudine. Nella maggior parte della pittura metafisica, e in ogni sezione di Submachine, non si trova alcuna presenza umana. In Submachine, tuttavia, restano tracce anche recenti, il che è paradossale rispetto alla decrepitezza degli ambienti. La maggior parte della storia viene narrata tramite note, lasciate indietro da personaggi più sfortunati e morti da tempo, o costretti a fuggire. L’unico contatto umano della serie avviene tramite computer, ed è unilaterale, dal momento che il nostro eroe non possiede una tastiera. L’isolamento è il potere più grande della Submachine, la macchina “nemica”, dovuto alla sua immensità e alla sua abilità nel crescere ed espandersi, separando e polverizzando per sempre allo stesso modo i pochi umani e gli oggetti. La sensazione di solitudine in De Chirico, invece, deriva da una sensazione surreale di familiarità. De Chirico rappresentava gli ambienti come visti dal finestrino di un treno, spiegando di voler riprodurre quella sensazione che si prova quando, passando vicino a una città, la si sente più familiare delle persone che ci vivono. Questo mappa dentro ognuno una rappresentazione intima del luogo, da cui sono esclusi i non-familiari, ovvero tutti gli altri. La sensazione di familiarità che le location di Submachine comunicano è invece legata alla disperazione del braccato, di quello che, perso nel bosco, riconosce con orrore di aver girato in tondo per ore e ore.

Infine, l’ultima caratteristica comune è il ruolo di primo piano dato agli oggetti. Come nelle “vite silenti” o nella serie dell’”oggetto misterioso” di De Chirico, nelle quali gli oggetti vengono messi su un palco a dispetto delle figure umane che vengono relegate senza volto sullo sfondo, in Submachine gli oggetti sono fondamentali. Infatti, quale installazione può dare maggior rilievo a oggetti comuni più di un gioco per vincere il quale bisogna sfruttare ciò che si trova e usarlo per interagire con l’ambiente circostante? Tutto ciò che di utile esiste in Submachine è un oggetto, una nota o uno schema, praticamente non esistono personaggi secondari, o se ci sono, ci si interagisce solo tramite note ed essi rimangono invisibili per tutta la serie. Al contrario le statue, le rappresentazioni e i macchinari in vago stile steampunksono onnipresenti, facendo una mimica di ciò che ci si aspetterebbe, ovvero il mondo “vero” al di là della Submachine (è tuttavia suggerito nel corso della storia che il mondo “vero” non sia una realtà esterna alla Submachine). Per la loro utilità e addirittura il senso di “compagnia” che se ne può trarre, – in fondo, sono gli unici alleati del giocatore contro un triste destino – gli oggetti sono umanizzati in Submachine, e questo deriva direttamente dall’umanizzazione in una sorta di nemico invincibile della Submachine stessa, che, lungi dall’essere semplicemente un’unità virtuale, come si suppone che sia, è un avversario, astuto e dalle immense risorse, che regna su un infinito spazio in cui il rapporto tra oggetti e umani è rovesciato, e l’unico suono che si sente, è il rumore di cigolii, muoversi di macchine, sinfonie non umane che corredano il quadro metafisico che è questo gioco. De Chirico ha rappresentato “gli archeologi”, un tema ricorrente della sua pittura, come uomini “ripieni” o composti da oggetti, elementi architettonici principalmente. Gli “archeologi” sono più che mai il punto di incontro tra il pittore e Submachine, rappresentando il tema della familiarità interiore, il “possedere” in modo univoco un particolare luogo o città, una ricorrente umanizzazione dell’inanimato, e, al contrario, una perdita di definizione e un oggettivizzazione, nel senso più letterale, della figura animata, che, così come il protagonista di Submachine, viene ridotta a un inventario di oggetti.

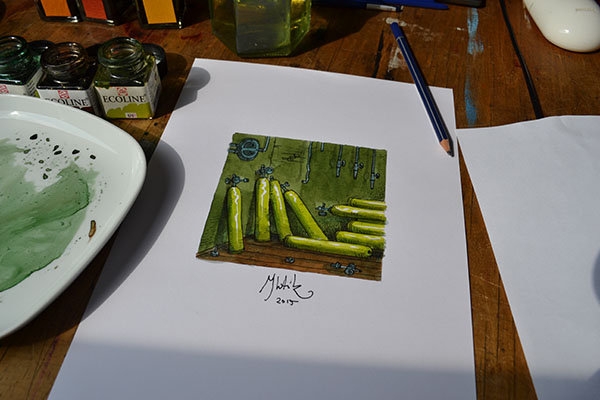

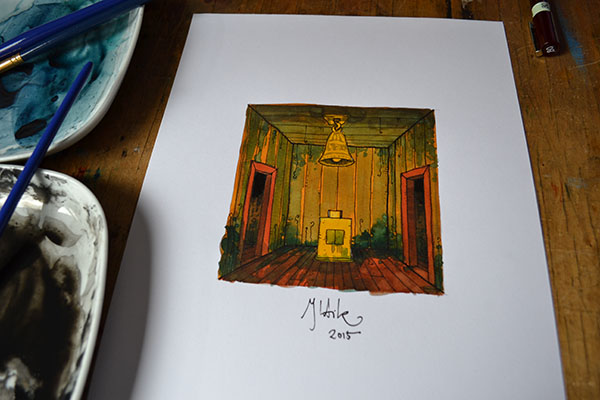

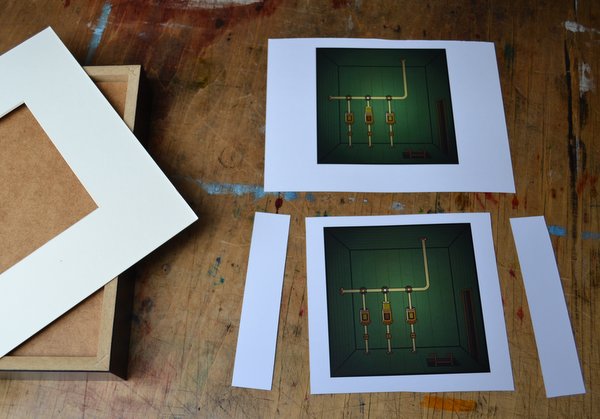

Submachine: FLF Redux HD

December 15, 2014

This is the game about memories, how they fade away, trick us or straight up lie to us.

Do you remember this game? Are you sure?

Try this version – you might not recognize it. Did you really hear this music? Is it changed? Or maybe it was there all along… I don’t remember anymore. One thing I know for sure – those pictures… I recognize them, they’re… from my past, my ancestors. I’ve seen them so many times, but were they here before? Is it possible that somebody changed them? Did I change them?

There’s a machine I haven’t seen before. There’s a room I haven’t been to, but I could swear I did. My memory about this game is murky. That’s how I see this game now. That’s the one I did so many years ago. Or is it?…

Well, this is it. The last Submachine game to be turned into HD version. This whole process rounded up nicely to a year-long project, where there was an HD game every month. Now the library is complete, I can move on to creating Submachine 10 and prepare a bundle of all of them for next year’s anniversary.

The stage for Submachine 10: the Exit is set.

« Previous Page — Next Page »